Wine Teeth by Emily Harman

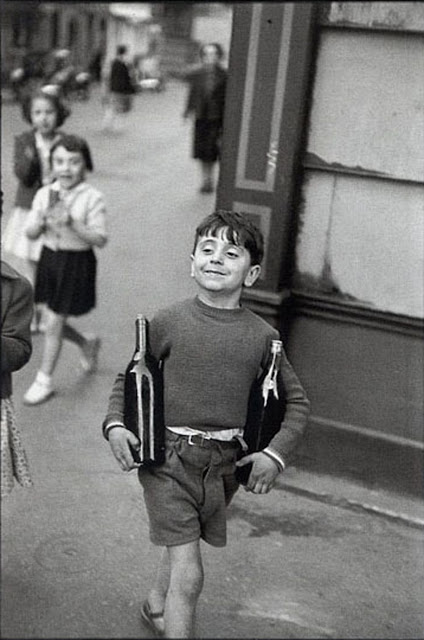

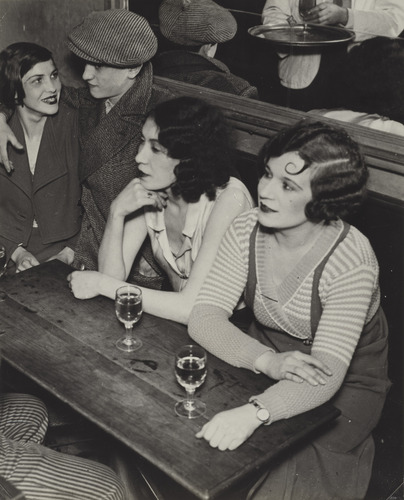

It has been commonplace since the beginning of time (in wine terms that is!) to see wine drinkers with teeth that have been eroded away and stained by their regular wine tasting and drinking habits. At parties, bars and wine tastings it is often no challenge to identify those who have been enjoying red wine.

I guess in every day life it is not a huge concern. When you work in a wine role, you could be tasting anywhere between ten and two hundred wines in one day, sometimes more. Reams of wine know how is shared freely amongst everyone the wine community. Yet nothing is passed down to you on what to do to maintain the one set of adult teeth you are given.

It was not until I lived in Melbourne that I was fortunate enough to find a very meticulous dentist, who insisted on teaching me new ways to look after my teeth. He quizzed me on everything relating to my dental hygiene, all my wine habits (both social and professional) and how all these overlapped with each other.

I remember recounting a tasting I went to earlier that week. It was a masterclass on wines from Heathcote. For those who have yet to experience these wines, they are a brilliant alternative for those who love the wines from the Barossa Valley. The wines are rich and full bodied – making them some of the best candidates for staining teeth from white to black after a few sips.

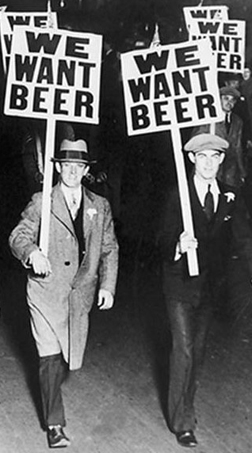

After the tasting I was due to work at Attica that evening and couldn’t bare the thought of any of our guests catching a glimpse of my teeth so I brushed my teeth until there was no trace of red wine to be seen. This wasn’t the first time either.

It turns out that brushing your teeth immediately after drinking or tasting wine is the worst thing you can do to your teeth and the enamel to protect them.

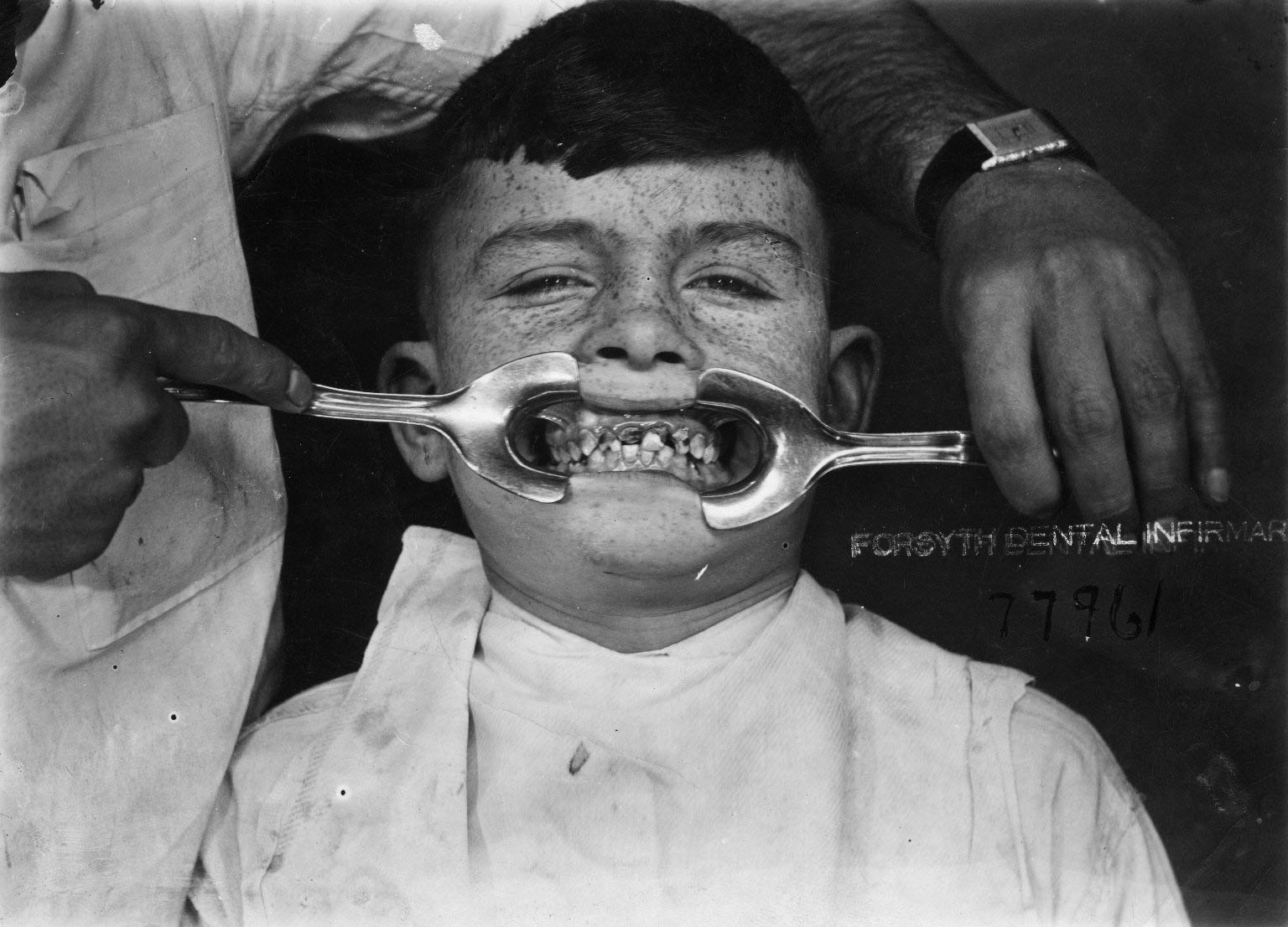

It is common knowledge that soft drinks are terrible for your teeth. It is often assumed that this is because of their high levels of sugar, but the high levels of acid found in these are also a big problem. Further to this the bacteria in our mouths use any sugar we consume to produce acid. When a tooth is exposed to acid regularly (for example if you regularly drink or taste wine), the frequent acid attacks cause the enamel to lose minerals.

Due to the levels of acid in all wine, brushing immediately means you are in effect brushing that acid onto your teeth so with every brush you are damaging your protective layer of enamel.

The enamel on our teeth is a one time only deal. So once it is gone, it is never coming back.

So what can be done?

- Daily flossing – this is vital to keep your breath fresh and to reduce any staining in between your teeth.

- Drinking and rinsing with water whilst tasting wine – water has a higher pH than wine, this can help to balance the acid in your mouth – meaning the acid has less chance of attacking your teeth!

- Avoid brushing soon after tasting and drinking.

- Use fluoride rich toothpastes and products. Fluoride not only strengthens enamel but it also reduces plaque bacteria’s from producing acid that will cause the decay. Toothpastes such as Pronamel are designed to help reduce the damage of acid wear on teeth. I also use Tooth Mousse overnight, this is a crème that you leave on your teeth to help keep your teeth full of minerals.